“What has failed,” says Culinary Union spokesperson Bethany Khan, “is the current practice of letting huge out-of-town corporations continue to gouge working people on rent.”

The Culinary Union – a major political player in Nevada that purports to represent casino workers – was behind a failed initiative last year in North Las Vegas that would have imposed a price-fixing scheme for housing called “rent control.”

The union was unable to collect enough signatures to place the measure on the ballot, but has now shifted its focus to the Clark and Washoe County commissions, where it hopes friendly commissioners will enact county-wide rent control ordinances.

Former governor Steve Sisolak also indicated last year that rent control could become a priority for state lawmakers in 2023, and, indeed, the Senate Committee on Government Affairs has introduced legislation authorizing local governments to enact rent control measures.

Rent control can take a variety of forms. In its strictest form, property owners are barred from raising rental prices on housing units subject to the control over the entire tenure of any particular tenant.

Slightly more lenient schemes allow the owner to increase rates up to a maximum percentage each year or may make adjustments for inflation. The Culinary Union’s proposals would allow rents to increase annually by the rate of inflation or 5 percent, whichever is lower.

In a period of rapid inflation – as the United States has experienced following governmental orders to halt the production of goods in 2020 while nearly doubling the money supply – Culinary’s proposal would imply a declining price in real rents.

In a period of rapid inflation – as the United States has experienced following governmental orders to halt the production of goods in 2020 while nearly doubling the money supply – Culinary’s proposal would imply a declining price in real rents.

For decades, there has been universal agreement that rent control destroys the incentive for property owners to maintain controlled properties and dissuades the construction of new housing within a controlled jurisdiction.

As economist Assar Lindbeck famously said, “In many cases, rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city – except for bombing.”

Empirical analyses have overwhelmingly validated these concerns. A 2017 review of rent control policies in San Francisco shows that renters of controlled units were 20 percent more likely to remain in those units to benefit from below-market rental rates.

Landlords responded by reducing the supply of rental units by 15 percent, leading to a city-wide rent increase of 5.1 percent that largely fell on renters on non-controlled units.

A 2012 study examined the effects of ending rent control in Cambridge, Mass., after it had been in place for a quarter-century. Turnover of residential units increased sharply as renters who had put off relocating finally elected to do so, but housing construction also came roaring back to the city as new housing starts more than doubled on an annual basis.

Without price controls in place, the value of rental housing as an asset increased by 18 to 25 percent across the city, and even non-controlled units appreciated as owners of controlled units had renewed reason to invest into their income-generating properties.

A 2022 study shows that rent control actually results in a regressive wealth transfer – counter to the assertions of proponents. It examined the imposition of rent control in St. Paul, Minn., in 2021 and determined the policy caused property values to instantly decline by 6-7 percent.

The tenants who gained most from below-market rents were disproportionately white and had higher incomes while the property owners who suffered the most had lower incomes and were more likely to be minorities. Thus, the impact of the law was the opposite of its declared intent.

Put simply, rent control makes it harder to find an apartment. Builders stop constructing new apartments and small family owners may decide to use the space for guests, or an art studio.

Residents of controlled units do not give those units up, although those units may eventually fall into disrepair because owners stop investing into them. In the long run, the result is even higher prices.

Yet, since 2019, California, Oregon and the District of Columbia have all enacted new, statewide rent control laws. A key impetus is the simple recognition that housing costs have risen rapidly in recent years.

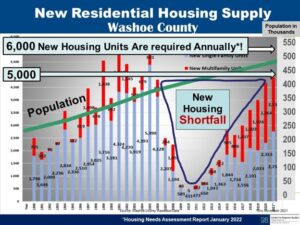

However, the evidence indicates that rental increases have been driven primarily by a dearth of supply. A data analysis produced by the University of Nevada Center for Regional Studies (reproduced below) shows that the construction of new housing units trailed off sharply following the 2007-09 recession, failing to keep pace with continued population growth.

The result has been a sharp rise in rental prices, amounting to an average rise of 19 percent across the state between 2015 and 2020, according to Census data reported by the Nevada Housing Division.

A number of regulatory reasons contribute to this paucity of new housing units, as detailed in Nevada Policy’s report, “The Construction of a Crisis,” led by the lack of land available for private development.

The true path to easing housing costs is not to enact a price-fixing scheme but to remove obstacles to building new supply.